At the end of World War II, the Kaiser Wilhelm Society was renamed the Max Planck Society, and the institutes associated with the Kaiser Wilhelm Society were renamed "Max Planck" institutes. The records that were archived under the former Kaiser Wilhelm Society and its institutes were placed in the Max Planck Society Archives. What happened to the records in this archive?

Research materials related to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics, including personnel, photographs, etc., are very difficult to come by. Indeed, information, including photographs of now-deceased researchers, are effectively "classified" (unavailable). This article illuminates why these research materials are difficult to access.

"A common goal of all researchers is to piece together who ordered the killings to commence in any given case. If in the twentieth century these mass murders were usually state-sponsored or at least officially sanctioned, who made decisions? What were their motives? These questions are particularly relevant if we want to hold leaders responsible for genocides or other grave human rights abuses before international courts. The problem for historians and jurists is that leaders and their agents try, usually with considerable success, to cover up their crimes and to destroy the evidence. Moreover, some states continue to deny crimes, including cases of mass murder and even genocide, committed by their predecessors. They also limit access to their archives and even persecute or threaten researchers. When scholars are finally granted access to their archives, they often find that evidence has been 'laundered' or destroyed. So reconstructing the decision-making process is often no easy task." 1

The Max Planck Society Archive has become the repository for records of the former Kaiser Wilhelm Society and its associated institutes, created during the Second and Third Reichs. After World War II, people such as Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer (the last Director of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics), sought to protect records and photographs from what he perceived to be "the enemies" of Germany. (A written statement to this effect exists, made by Verschauer himself during the closing days of the Third Reich.) In fact, some of these records were hidden by Verschauer in his own home. Thus, before the Third Reich fell, attempts were already being made to hide records. The following statements by an unbiased historian show that records were removed and destroyed, apparently not collected (to avoid their being in the record), or not made available to the public.

Aside from making many of the records of the Second and Third Reichs inaccessible, inasmuch as the records are also related to the Holocaust, these actions also amount to Holocaust denial. 2 In addition, withholding and destroying historic German documents is an insult to the people of Germany, especially those citizens who opposed National Socialism and were murdered in Nazi concentration camps. The Max Planck Society and its affiliates is supported by German taxes: thus, such censorship is a violation of German state laws. 3

"When the war came to an end, information about what had actually transpired in the camps and occupied territories became public knowledge only over a period of years, and much remains undiscovered and not discussed. The role of anthropologists in the Third Reich was perhaps better known among the populace than reported in the literature, as the following anecdotes illustrate." 4

"In the 1980s, Benno Muller-Hill tried to gain access to the German Research Society (Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft, or DFG) records, a primary source of funding of anthropological and other scientific projects in the Third Reich. 'As I tried to get the DFG records in 1981, I was told by the staff that the DFG in the Third Reich was not called the DFG and that access to the files was not granted: the files on the DFG were not available on principle. He was told that he would be sued if he persisted." 5

"[...] a variety of German laws prohibited access to certain files and documents for fifty years following the war, thus they became available only in 1995. These were primarily files dealing with individuals. [...] [M]any of the documents and much of the information needed to create a history of the era were destroyed, often intentionally." 6

"[...] Many of the documents that were placed in archives are now missing or have never been collected. In a personal conversation in the early 1990s, the American director of the Berlin Document Center (BDC) told me that he felt certain that some Germans had made connections with the BDC staff for the purpose of destroying damaging documentation." 7

"[...] [T]hose who use the MPGA [Max Planck Society Archives] must have all copies of materials inspected personally by the director, as I learned. When I used the archives for the first time, I was pleased to find that I could copy documents myself at a copy machine in the hallway. Having the documents in hand would be helpful, as I was preparing to leave Berlin. Much to my surprise, the reading room supervisor told me that I could not take copies with me at that time, that first they would have to be inspected by the director. It was the rule." 8

"[...] On a visit to the archives of the museum's anthropology department in 2001, I was met by a staff member of the Department of Biological Anthropology with both interest and reserve. She knew of my work with the NAA-SI [National Anthropological Archives (Smithsonian)] and the documents I had archived there. After a brief meeting with the staff, I was told I could look at the literature housed in the archive only if I could name what I wanted to see; I was told that I would not be given access to the card file and could see no records of the IDO [Institute for German Work in the East] because the staff themselves were working on them and hoped to publish them. I could not have access to information about the post-war careers of the IDO members." 9

The historian Lucy Dawidowicz 14 has created a "scientific" form of historiography based upon the idea of "continuity". This idea of continuity allows the historian to examine the present in comparison with the past, or, alternatively, to examine the past in order to understand the present and future. Using this scientific or mathematical form of continuity, it is possible to examine historical events such as the Holocaust and show that the Holocaust is NOT an aberration, as German anti-Semitism has a long history; similarly, that the long history of German anti-Semitism is likely to continue. Dawidowicz then examines how the historians of various countries deal with the Holocaust. Various methods of dealing with the Holocaust are treated:

Thus Dawidowicz shows that one way to deal with the problem in historiography is to deny continuity. A major way to accomplish this denial of historical fact is to censor the facts, to refuse to collect documents, etc. Dawidowicz focuses on the Holocaust, but the problem of continuity applies to more than the Holocaust and the period of National Socialism in Germany; it also applies to the genocide of the Herero and Nama peoples in Deutsch Südwestafrika (German South West Africa), as well as other colonial histories. Dawidowicz is not the only historian to describe continuity as being a major factor in historiography. For an example of continuity as a factor in the medieval foundation of modern colonialism, as well as German medieval colonialism, click here. Colonialism, slavery and Christianity have existed in Europe for over a thousand years, and must be considered part of the European cultural heritage.

One must bear in mind that to apply Dawidowicz' theory of historical continuity (over time), technically predicate functions 16 over a time variable are required. This implies an understanding of a synchronic vs. diasynchronic analysis 17 view (sometimes subsumed under "Historical Materialism".) 18, 19, 20, 21, 22 Gretchen E. Schafft has been repeatedly referenced, noting how much resistance she encountered while trying to exhume the record of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes. These forms of censorship have been mentioned above in this article, but the problem is obviously more extensive, insofar as it applies not just to information about gypsies and Jews, and the Kaiser Wilhelm Institutes, but applies to the history of all countries. For example, in "The angel of death has descended violently among them", historian Casper Erichsen recounts the censorship he encountered at the Namibian National Archives from Head Archivist Brigitte Lau, when researching information about the Herero and Namaqua Genocide.

"The history of Namibia's concentration camps has long been overlooked and largely forgotten in the existing historiography about the 1904-08 anti-colonial wars. Most theses or histories dealing with these anti-colonial wars at best only make passing reference to concentration camps and the prisoners kept there. Illustrating this amnesia, the former Head of the National Archives of Namibia, the late Brigitte Lau, remarked in 1989 that existing records of Swakopmund and Windhoek were 'silent' about the camps thereby posing questions about their existence.

"In acknowledging that information about the camps has been scarce in the close to 100 years following their formal closing in 1908, this chapter seeks to retrace the history of the concentration camps and to answer the very basic questions about them, more specifically: when, where and what they were. The chapter goes a step further in looking at patterns in terms of treatment of prisoners and what internment in the camps entailed for these people.

"Ironically the bulk of the research for this chapter was conducted in what is today known as the Brigitte Lau Reading Room at the National Archives of Namibia and the records were not all that silent." 23

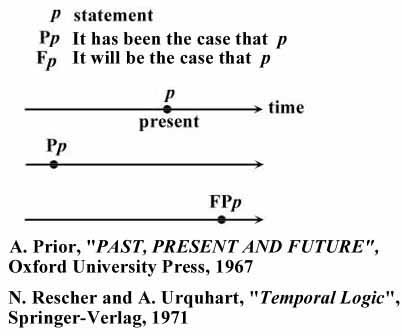

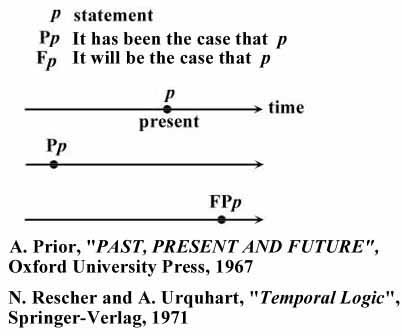

What does the above discussion -- true or not -- have to do with difficulty in accessing materials at the Max Planck Society Archive? Let us examine the following. Any normal, thoughtful person has thought processes that can travel back and forth in time. For example, if one wanted to censor the history of National Socialism in Germany during the Third Reich, one might wonder what ideas prior to the Third Reich should be censored in turn. One might find a precedent to the actions of Facism in what transpired in Deutsch Südwestafrika. This in turn might imply a necessity to censor the ways in which Deutsch Südwestafrika led to ideas during the Third Reich. Thus, finally, the realization in the present time, that aspects of the history of Deutsch Südwestafrika must be censored, in order to censor the origins of Nazi racism. Not only does this require thought (as a function of time), but also the 'dialectic' of moving back and forth in time: a use of Temporal (or Chronological) Modal Logics, Temporal Logics or Tense Modal Logics. 24, 25, 26

Invoking Lucy Dawidowicz's idea of continuity, one would suspect a relationship might exist between the revisionism found in Brigitte Lau's view of the history of Deutsch Südwestafrika and what happened a few years later, during the rise of National Socialism. Indeed, there is a clear and undeniable link:

"According to Arendt, H. (1975) The origins of totalitarianism. New York: Harcourt Brace, 'African colonial possessions became the most fertile soil for the flowering of what later was to become the Nazi elite. Here they had seen with their own eyes how peoples could be converted into races and how, simply by taking the initiative in this process, one might push one's own people into the position of the master race. Here they were cured of the illusion that the historical process is necessarily "progressive".' " 27

Bear in mind that people such as Eugen Fischer worked in both Deutsch Südwestafrika during the Second Reich as well and at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics (KWI-A) during the Third Reich. He studied the skulls of the Rehoboth Basters in both Deutsch Südwestafrika during the Second Reich, and at the KWI-A during the Third Reich — later to become a part of the Max Planck Society, with its censored archive (as noted by Gretchen E. Schafft).

Synchronic phenomena are static, and are not viewed as changing in

time (or are viewed only at one moment of time).

Diasychronic phenomena are dynamic, and are viewed as being subject

to change over time.

While "time" is the most common parameter, location, place or position are

sometimes also used. For example, Lusotropicalism is a theory of race that

is diasychronic in that it constructs a theory of racism that is based on

location (the Tropics). Thus, making use of standard First-order logic or

Predicate logic:

| Object | Type of Object | Example | Classification |

|---|---|---|---|

| p | proposition | "New World slaves during the 17th century were not permitted to carry firearms in Surinam." | synchronic (static) |

| p(t) | monadic predicate function | "New World slaves during the t century were not permitted to carry firearms in Surinam." | diasynchronic (dynamic in time) |

| p(l) | monadic predicate function | "New World slaves during the 17th century were not permitted to carry firearms in l." | diasynchronic (dynamic in location) |

| p (t, l) | dyadic predicate function | "New World slaves during the t century were not permitted to carry firearms in l." | diasynchronic (dynamic in time and location) |

When dealing with a proposition, as usual, the proposition is either true

or false. When dealing with a predicate function as different instances of

time or location are used, the predicate functions may vary in truth.

Thus, p(t) becomes:

"New World slaves during the 19th century were not permitted to carry firearms in Surinam."

and p(l), with location l = Brazil, becomes:

"New World slaves during the 17th century were not permitted to carry firearms in Brazil."

and p(t,l), with time t = 18th and location l = Cayenne, becomes:

"New World slaves during the 18th century were not permitted to carry firearms in Cayenne."

To do a comparative temporal analysis of slavery in Demararra, one might consider p(t, Demararra), or

"New World slaves during the t century were not permitted to carry firearms in Demararra."

Thus, comparative studies in slavery comparing different times or comparative studies in slavery in different locations would require a diasynchronic view.

© Copyright 2006 - 2019

The Esther M. Zimmer Lederberg Trust

Web Site Terms of Use

Web Site Terms of Use